In praise of music with words: Serge by The Herbaliser

Having spent most of my life enjoying dance music from all over the world, I’ve never been particularly concerned about lyrics. Dance music is about rhythm, groove, swing, however you want to describe it. Drums that thump, melodies that uplift. If there’s a lyric in a language I can understand then that’s a bonus. Besides, how can you prioritise lyrics when so many dance tracks are instrumentals?

Occasionally, this rule is flipped on its head and I fall for the words as heavily as the beats. Often it’s when I least expect it. Sometimes a lyric creeps up on me after years of ignorance. A tune I’ve long enjoyed for the vibe suddenly reveals a sentiment that connects. The Herbaliser’s Serge is a good example.

I first heard Serge nearly ten years ago, which was nearly ten years after it was released. It took me until a year ago to fully appreciate the genius of it. I can’t remember how I came across the track but I was instantly hooked. Living in New York, it was a welcome connection to Europe – a combination of UK beats and French lyrics – at a point when my family was beginning to think about moving back to London.

A song on the band’s 2005 album, Take London, Serge is an addictive cocktail of unexpected ingredients. An opening lazy baseline is soon joined by a Deliverance-style plucked banjo. A tambourine dawdles into the mix and then – bam – a thudding drum accompaniment and an other-worldly, vibrating synth join in. This concoction chugs along for a few bars before Philippe Katerine arrives to deliver a monotone monologue. In French. It’s all very seductive if, like me, you love downtempo grooves and moody spoken word.

At the time I assumed it was about Serge Gainsbourg, without understanding Katerine. With that title and then the Gallic lyric, how could it not be? I didn’t care that I didn’t understand. Like all the Brazilian music I love without knowing any Portuguese, Serge just sounded great. The lolling, insistent metre combined with Katerine’s laconic, melancholic delivery. Perfect.

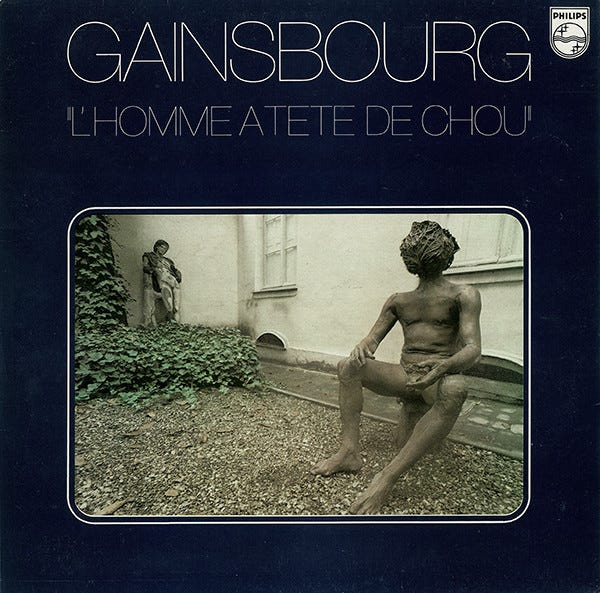

A few years later I discovered that the music is a reworking of a Gainsbourg track, Flash Forward, from L’Homme à Tête de Chou, and I fell for it even further. What really impressed was that the banjo was not part of library don Alan Hawkshaw’s original arrangement. At least, no banjo is mentioned in the Tête de Chou credits, and a faint plucked acoustic or electric guitar, when detectable, is way down in the mix. For me, it’s this wonky juxtaposition that really lifts the music of Serge to surpass its source. Kudos to The Herbaliser. It’s a magnificent touch.

Then, last year, I finally got round to deciphering those lyrics. I had – in the intervening years – become aware of Philippe Katerine. Originally known as a pop provocateur, he’s now a multi-hyphenate cultural fixture in France (and the guy from that moment in the Paris Olympics opening ceremony). Singer, songwriter, actor, painter…he once described himself as a tourist in all these fields, the kind of tourist that devours each city they visit.

Knowing Katerine better as an artist made me want to understand what he’d contributed to the track. At that point, my mind was truly blown. The words that he drawls in Serge describe an encounter with Gainsbourg on the streets of Paris’ Latin Quarter. Katerine spots the older musician and follows him into a tobacconist where Gainsbourg buys cigarettes. He continues to follow him back to Gainsbourg’s house on Rue de Verneuil. But he doesn’t speak to him. What could he say? That he likes his work? That he too makes music? What the hell would Gainsbourg have cared if he’d written some songs? Then three days later, Gainsbourg dies. Katerine wonders if he witnessed him buy his last cigarette. It’s achingly poignant. But is it true? Interviewed by Marie-Hélène Poitras, for the magazine Voir, shortly after the release of Take London, Katerine dodged the answer:

“I guess it’s some kind of dream. Sometimes I have trouble telling the difference between dream and reality, knowing what really happened. I guess it’s true since I wrote it, but I don’t know at all. I have trouble telling the difference between what is true and what is false: that’s my eternal problem.”

It’s all these layers that make Serge work so well. The unexpected instrumentation, the regret-soaked lyrics, the narrative that mirrors the Gainsbourg source, and finally the blurring of fact and fiction. Just listen…

(An version of this article first appeared in the ever wonderful Ban Ban Ton Ton.)